Chapter 28 Pots, Trays, and Slabs

Bonsai trees will spend their lives in several different types of containers. Most trees start out as nursery stock in black plastic pots like the ones you see in garden centers. Well-chosen training containers help trees develop desirable features more quickly and keep trees healthier. As the tree matures, a good show container complements the tree’s shape and style, and species.

First and foremost, ALL bonsai containers need to drain well. A container that does not drain well increases the chances of root rot and other diseases. The container should be large enough to contain the root mass of the tree without constricting it or forcing roots to bend against the container walls.

28.1 Options For Training Containers

28.1.1 Plastic Nursery Pots

Standard-sized pots are not the right dimensions for training bonsai, but they can be modified easily to make training containers. For example a Trade 5 standard (trade 5-gallon) high-density polyethylene nursery pot measures 11.8 inches in diameter and 11 inches high. A Trade #5 squat (5-gallon mum) pot is shorter, but still measures 13.8 inches in diameter and 9.9 inches high. As a general practice, I try to keep my training containers 3-5 times broader than high. So even a squat standard pot still is too deep.

The easiest way to turn a standard pot into a training pot is to cut it down.

| Std. Pot Size | Avg. Diameter | Std. Height | Final Cut Down Height |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 Squat | 15 inches | 12 inches | 3-5 inches |

| Trade 10 | 15.8 inches | 15 inches | 3-5 inches |

| 10 Squat | 18.4 inches | 12.1 inches | 4-6 inches |

| 15 Squat | 18.4 inches | 15.1 inches | 4-6 inches |

| Trade 25 | 24 inches | 18.1 inches | 5-7 inches |

If you do not have any larger containers to spare, ask nurseries if they have any old containers they could share or sell you for a few dollars.

Most nursery containers are blow-molded plastic, so the walls of cut-down pots can be very flexible. If this is a problem, I take the top half that I just removed and slide it down inside of the pot to reinforce it before adding soil.

28.1.2 Landscape Fabric Bags

I get very good results from fabric bags as training containers, especially for tree that do not have well-developed fibrous roots. The “pots” are sewn from heavy-weight polyester landscape fabric. As roots grow they hit the woven fibers and branch rather than turn. Any roots that do pass through the fabric are exposed to air, and die back on their own. When it is time to repot a tree the bag is pulled off the root ball, which breaks off the very tips of the feeder roots and triggers a flush of new root growth and branching.

Commercial fabric bags come in different grades; the best are rated for up to 20 years and can be reused several times. They are not cheap, but are not outrageous either. I have several that I have reused for going on 15 years now. Less expensive versions still last 3-5 years without degrading. That is plenty of time for a tree in training to build a thick mass of fibrous roots.

Like plastic nursery pots, fabric bags come in standard sizes that are too deep for bonsai training. Rather than cut the bags off, I simply fold the fabric sides in half. This brings them down to the right ratio of diameter to height.

One caveat when using fabric bags is that they dry out more quickly than plastic pots. When watering, you need to spray them on the outside surfaces as well as watering from above.

Read the page on Professional Nursery Practices to learn more about these types of pots.

1.

2.

3.

4.

SmartPot, the original manufacturer of fabric bag pots. Their bags are made from a geo-textile fabric used as protective padding under pond liners. This type is rated for up to 20 years of continuous use. 1. A new pot, still folded. 2. The unfolded bag. When filled, this bag holds 15 gallons of soil or media. A folded fabric bag (3,4). The manufactured bags are too tall for normal bonsai training containers. Rather than cut them down like plastic pots, the fabric bags can be folded down, which both reinforces the sides and allows for adjusting the volume if needed. Original images, by A. Daniel Johnson.

5.

6.

Kangaroo Pots are a newer entry into the market (5). They are made from recycled plastic, mainly bottles. They are rated for 3-5 years, but cost much less than geo-textile bags. This particular model has integrated carry handles (6). Original images, by A. Daniel Johnson.

7.

8.

28.1.3 Plastic Pans

Any variety of plastic pans can be repurposed for training pots. Personally I have settled on plastic dishpans as my standard training pots. They also double as my containers for starting tree seeds. I buy dishpans from The Dollar Store in bulk, usually 2-3 dozen at a time. These pans are about 9x13 inches at the top, and hold around 2 gallons of soil mix.

I drill 8-10 drainage holes in a stack of 10-12 pans all at one time using a 1/2-inch chisel bit. I’ve learned a couple tricks for drilling the holes.

- Pans tend to splinter if drilled when they are cold. In spring I bring the stack indoors to warm up or leave them in the sun for few hours before drilling.

- Some manufacturing lots of plastic pans are more brittle and tend to split and crack rather than drilling cleanly. When this happens I drill fewer pans at a time.

- If pans still break or split, I cut a piece of landscape fabric ~2 inches larger than the pan and place it in the bottom with the excess fabric extending up the inside walls. This keeps the soil from falling out of the holes.

9.

10.

11.

A standard plastic dishpan. 9. Side view. 10. A dishpan with cleanly drilled holes. 11. A dishpan from a brittle lot, showing how they can break rather than drill cleanly. Original image, by A. Daniel Johnson.

For larger trees I use either 23 x 16 x 6 inch high (28 qt.) rectangular storage boxes or 27 x 20 x 6 inch high (40 qt.) black mortar mixing tubs from a home improvement store, again with plenty of 1/2-inch drainage holes. Filled with soil mix, these pans weigh 50 pounds or more. They are the largest containers I can move comfortably without help.

In the past I’ve also used kitty litter pans, plastic oil change pans, and animal feed pans. They all worked well enough, but were hard to find in large numbers consistently.

28.1.4 Training Boxes

A lot of growers like to train their trees in wooden boxes. Personally I quit using wood boxes because I did not have time to make all I needed. This is how I used to make conveniently-sized 18-inch square wooden boxes. They last 5-7 years before they begin to rot.

- Buy 2, 6-foot long piece of exterior appearance grade pressure-treated wood, 0.5 inches thick & ~3 inches wide.

- Cut each plank into 4 pieces: 2 pieces 17.5 inches long, and 2 pieces 18.5 inches long.

- Pre-drill 2 pilot holes in ONE end of each 17.5-inch piece.

- Use 1-inch exterior deck screws to assemble the 4 pieces into a box exactly 18 inches square.

- Space the 4, 18.5-inch pieces evenly to form a slatted bottom for the box.

Yes, the bottom slats are longer than the box is square. I like for the bottom slats to extend a bit beyond the edge of the box so I can drill the anchor holes for the screws a bit further in from the ends of the slats. This makes them less likely to split.

- Attach the bottom slats with deck screws.

- To keep in the soil, line the box with 1-2 layers of landscape cloth, stapled in place.

28.1.5 Plastic and Mica Bonsai Pots

Mica pots are a modern product that is mass produced mainly in Korea. They are composed of 85% powdered mineral mica, 5% graphite, and 10% polyethylene. These durable training pots stand up to repeated freezing and thawing, don’t break when dropped, and can be purchased in a variety of sizes and shapes.

A mica pot being used as a “suiban,” or shallow tray used to display a “suiseki” (viewing stone.) Often suiseki are placed into sand or fine grit for display. This particular example has moss instead. The stone is reminiscent of a mountain scene I saw in the Canadian Rockies, with a bare stone massif standing over a valley blanketed with conifers. Eventually this suiseki may be moved into a permanent ceramic tray. Original photo by Dan Johnson.

Plastic bonsai training pots are available in a variety of sizes, and cost only a few dollars each. Original image, by A. Daniel Johnson.

28.2 Ceramic Show Containers

Japan, China, and Korea are the main centers for production of show-quality pots. However many places in Asia, the US, and Europe have rich pottery traditions, with talented artists creating beautiful bonsai pots.

Regardless of its origin, the final “show” pot is meant to frame the bonsai. So like a fram on a painting, the shape, color and size of a pot need to harmonize with the tree. These guidelines are paraphrased from Allen C. Roffey, author of The Bonsai Primer (www.bonsaiprimer.com/pots/pots.html.) Remember, these are general guidelines; choosing a pot that creates a pleasing sense of balance is the most important goal.

Shape and Color

- Conifers tend to be planted in plain, earth colored pots

- Deciduous and flowering trees are planted in a glazed pot that is colored either to provide contrast in winter when the trees are bare, or complements the tree at a particular time of year.

- A rectangular pot isolates a tree, so is better suited for a more formal style or heavier trunk. A shallower, oval pot is more harmonious with the landscape, so is better for “softer” styles.

- Use pots with sharper angles for trees with sharper angles or needle-like foliage. Use more rounded pots for trees with more flowing movement.

- Use a round “drum” style pot for bunjin style trees.

Size

- For single-trunk trees, choose a pot that is about as deep as the tree is wide across the nebari.

- The branches and foliage should extend out beyond the left and right sides of the pot, and beyond the back of the pot.

- For cascades, pick a pot with a top opening that is less than half the horizontal span of the tree, and is about half as deep as the vertical height of the tree. Remember that cascade trees are always displayed on stands, lifting the lowest part of the tree off the surface.

28.2.1 Types of Ceramic Pots - Tota-koda-whatta?

I admit the first time I heard someone mention “tokoname ware,” the significance was lost on me. Later I learned why tokoname ceramics are so highly regarded.

The major pottery making centers of Japan developed near the natural clay deposits. Differences in clay composition and local customs at these locations led to major and minor schools, or “old kilns,” some of which date back a millennium. One of the oldest and most influential of these “old kilns” is in Tokaname, a small city of ~50,000 in Aichi Prefecture. Even today it is a major ceramics manufacturing center, with both traditional and high-tech modern production facilities.

Tokoname ware is made with a high fired clay that is very long-lasting, making it ideal for pots that must endure temperature extremes. The area also is famous for ash glazes, which can be so subtle that the pot does not appear to be glazed at all.

Potters of other “old kiln” traditions also made beautiful pots suited for their local species. Do not reject a pot just because it is not Tokoname. To learn more about these other regions and styles, check out the Japanese Pottery Information Center at www.e-yakimono.net/guide/index.html.

Many US and European bonsai suppliers have Tokoname pots for sale, but be prepared for major sticker shock, especially if the pot is antique, or was signed by a well-regarded potter.

28.2.2 Houtoku

This is another widely known category of Japanese bonsai pots. These high-quality Japanese containers have been the mainstay for enthusiasts wanting traditional high-fired pottery.” Others rate them just a bit below Tokaname ware in quality (but still far above mass-produced Chinese pots), but with a much better price. Production is centered near Nagoya, Japan.

28.2.3 China and Korea

Korea and China were the original sources for most of Japan’s ceramics technology. In fact the style of kiln used for Tokoname and other traditional wares originated from Korea in the 1100’s.

China has a very rich ceramics heritage. Typically, most Chinese pottery is fully glazed, making the characteristics of the clay less important than the colors in the glaze. The exception to this are pots made in the Xixing region of Jiangsu provice, in eastern China. Clay has been mined from this region since the Song dynasty (960–1279.)

Xixing (also called Yixing or zisha) clay adapts extremely well to hand-building techniques. It is very fine-grained which allows potters to create highly polished surfaces on unglazed items. Like tokoname clay, it is fired at a very high temperature, making it very strong.

1.  2.

2.  3.

3.

If Xixing ware is glazed, it usually is a very simple colored utilitarian glaze.

Tan speckled and pale blue glazes. Link to original image 1; image 2.

Because they are not glazed, Yixing pots slowly wick moisture away from the roots, which reduces the likelihood of root rot. At the same time the pores hold small amounts of water and minerals, which smooths out the peaks and troughs of soil moisture and nutrient levels.

28.2.4 Specialty Potters

There are many well-known potters in the US and abroad who create containers that are one-of-a-kind works of art. These can be quite expensive, but remember that these containers have been individually hand-crafted, not mass produced. Some potters will even build containers for a specific tree on commission.

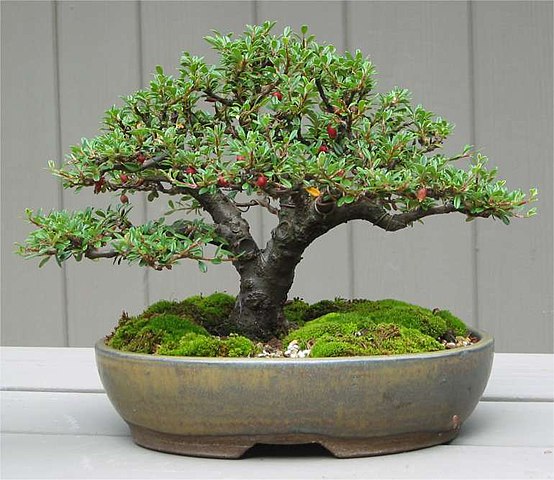

A shohin-sized cotoneaster, about 7 years old, in a Sara Raynor pot. Link to original image

I’ve listed several of these potters on the Sources and Suppliers page.

28.2.5 Slabs

Slabs are used mainly for large grove plantings and saikei-style scenes. Some artists use treated marine or exterior grade plywood that has been cut to a specific shape. Thin flat pieces of slate or other stone are also used.

More often the slab is manufactured. Less expensive slabs are made by casting glass fiber reinforced concrete. The exposed edges of these slabs tend to have a more natural look than the sawn edges of wood bases. Slabs also are made from pottery clay, then glazed and fired in the same way as pots would be. Some pottery slabs are made to look like natural stone or wood, while others have more decoratively finished edges.

Regardless of the material, slabs require some specialized techniques to contain the soil and ensure the trees are kept in place. These are described elsewhere..

A group planting on a rock slab. The trees are held in place by wires anchored to the surface with epoxy or superglue. The soil is contained by a layer of muck soil that forms a berm around the edge of the slab. Link to original image.