Chapter 49 Salvage Operations: Rescue and Repair Techniques

It’s inevitable to have trees that get damaged by browsing deer, are left un-watered for too long, or meet with some other mishap. Fortunately, there are some good techniques for dealing with these and other common mishaps. These horticultural “first aid” methods are not my own discoveries. When possible I will provide the source from which I learned about the technique. If you know the original source, let me know.

49.1 Desiccated Pots

No matter how I try, every summer I miss the occasional pot or stock tree as I water. If I find the leaves simply wilted, a drink of cool water usually is sufficient to revive the tree. If I do not see the leaves begin to rehydrate and return to normal within an hour or two, the tree may be near the permanent wilt point, when the tree becomes unable to draw up water. If the leaves have actually begun to dry up and become brittle, the tree definitely is near death. Either way, the tree is likely to die sans intervention.

I first read about this trick in the Bonsai Survival Manual, by Colin Lewis.

- If the tree is a broadleaf species, remove every leaf that is dried or brittle. If the leaves are merely wilted, wait a day to see if they revive before stripping them. Do not leave dead leaves on the tree, as they are a potential source of fungal infections.

- Immerse the entire pot in water so the soil is completely covered, and let it soak for 30 minutes to an hour to rehydrate the soil particles. (This also is a good way to eliminate chronic dry spots in large pots.)

- Place the pot at an angle so it drains thoroughly.

- Put the tree and pot into a large clear plastic bag.

- Insert bamboo stakes in the pot so the plastic bag is not touching any branches or leaves. (This discourages fungal rot).

- Close the bag with a twist tie, and place the tree in bright shade (NO DIRECT SUN).

- If you see fungus beginning to grow, remove the bag and spray the entire tree with a general fungicide, Then place the tree back into a clean bag. Otherwise, keep the tree in the bag until new buds begin to appear. Depending on the level of die-off, this may take a month or more.

- To harden the new growth, open the bag in the AM for an hour or so, then close it again. Every couple days extend the length of time the bag is open by an hour or two. When the bag is open for most of the daylight hours, remove it.

- Keep the tree in bright shade until it is growing well again.

49.2 Overheating

Even if a tree has enough water, soil temperature can place additional stress on it. The roots of a tree grown in the ground in full sun rarely experience temperatures much above 85oF, because the ground acts as an insulator. Trees in pots do not have this protection. Light-colored clay or glazed pots may not heat significantly in the sun, but the soil in a black plastic training or stock pot can reach 100-115oF.

Short-term symptoms of root heat stress include leaves that turn down rather than point out; unlike desiccation the leaves may still feel thick and fully hydrated. Poor growth and leaf die-back occur as the tree self-thins in order to reduce the amount of top mass to balance the weak roots. Long-term symptoms are easy to recognize: the tree is dead.

1.  2.

2.  3.

3.  4.

4.

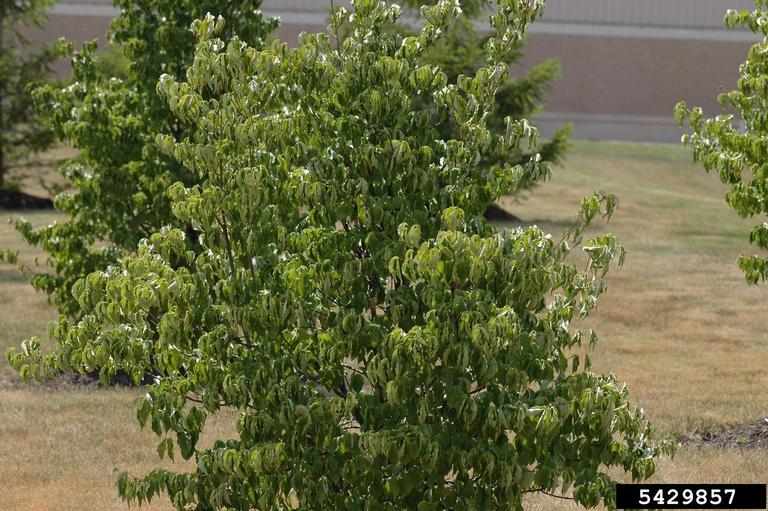

Image 1. Early signs of heat stress in dogwoods planted in full sun. Image 2. A later stage of abiotic, heat-induced leaf scorch. Image 3. Heat-stressed rhododendron with curled down-pointing leaves that indicate extreme heat or cold stress. Image 4. A Scots pine burned by drought and intense summer heat. Link to original of Image 1 by Brian Kunkel, University of Delaware, Bugwood.org; original of Image 2 by Cheryl Kaiser, University of Kentucky, Bugwood.org; original of Image 3 by Elizabeth McCarty, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org; original of Image 4 by Steven Katovich, Bugwood.org

Diagnosing overheating is simple. During the hottest part of the day, stick a wooden stake into a pot 1 inch, pull it out, then stick in your finger in the hole. If the soil feels warmer than your finger, it is too hot. Move the tree to a shadier or cooler spot.

Here are some other way to protect against overheating.

- When setting trees out in spring, pick locations that get mid-day shade in summer. Early in the season the leaf canopy is fairly open so will not block enough light to reduce growth, but in mid-summer, will provide vital cooling shade. Overall growth will also slow to compensate.

- Before you plant stock trees in black plastic pots, paint the outside with white or pale gray gloss paint. Let pots dry thoroughly before use. For existing trees, coat the pots with whitewash or white greenhouse window paint.

- Build a sand box for your trees. Using 1x6 lumber, create a 4’ x 8’ raised bed where you normally would have a bench. Fill the bed with white play sand, which reflects light. During high summer bury pots up to the rim in the sand, then soak the sand thoroughly with water. Evaporative cooling will keep the temperature of the pots well below critical levels. When you are done with your sand box for the year, cover it with a sheet of exterior grade plywood and fasten the edges with screws. This will keep the sand clean and ready for next year.

Like so many things in horticulture, there are many different opinions about the effects of heat on roots. For more information, I suggest this article: http://www.evergreengardenworks.com/rootheat.htm

49.3 Wet Pots & Root Rot

While desiccation can kill in 24 hours, over-watering is nearly as bad, killing a tree in 4-5 days. There is an ongoing debate on the bonsai forums just how susceptible trees are to root rot. Some say root rot fungus actively attacks and kills root. Others claim root rot is incidental, appearing only after the roots are already dead or dying. Either way, too much water or a pot that will not drain properly is going to suffocate the roots and kill a tree.

Examples of root rot due to overly wet soil. A. Overview of the roots of a Japanese maple seedling. The millipede (blue arrow) is NOT a sign of ill health. They are attracted to the decomposing bark. B. Root bark sleeves. One of the distinctive features of root rot in deciduous trees is that the bark on the roots breaks up into brown tubes surrounding the shrunken white core of the root. It is easy to mistake these for emerging new white roots, but the sleeves will slide along the root easily. C. Another sign of root rot is the lack of fine white feeder roots emerging from the larger structural roots. D. Root rot in conifers can present a little differently. This photo was taken in mid-summer, when the roots should have white or red swollen tips. Instead all of the roots are black and wiry all the way to their tips. Original photos by Dan Johnson

The simplest way to prevent over-watering is to monitor your trees regularly. Some drying is essential to good root health. If the top 1/2” of soil is dry, then water, but if it is not dry, wait. However, there are sometimes other causes for overly wet soil. It can be a symptom of decayed or compacted soil. The shape of some pots also makes them tend to hold excess water.

Early above-ground symptoms of over-watering and root rot can be subtle. Older leaves or needles begin to yellow, and entire branches or one side of a tree will begin to fail. If you lift the root ball from the pot, the fine roots should be reddish to pale yellow or white. Small feeder roots that are dark brown or may be rotting, particularly if they have a foul odor that is distinct from the surrounding soil. Trees that have been in a pot for several months should have a tight grip on the soil; an overly loose tree could indicate its roots are dying.

If you suspect a tree is suffering from overwatering, overpotting into a rescue tray with a wicking soil mixture can reduce the damage:

- Prepare a rescue tray that is at least twice as deep and half again as large in circumference as the pot the tree will be leaving. Cement mixing trays and dish pans are a good choice. Be sure to drill multiple drainage holes; you want as little standing residual water as possible.

- Prepare wicking soil mix that has a larger grain size and is 10-20% higher in non-organic matter than what the tree you are working with normally would use. For example, if you are working with a 12-inch tall juniper that has root rot, the soil mix you use normally might be 40% organic, and 60% fine chicken grit. To encourage the water to move quickly away from the roots, you need to prepare soil that is closer to what pines like (75% non-organic). You also should use the next larger size of grit if possible.

- Place a layer of fresh wicking soil in the bottom of the rescue tray that is of equal depth as the original pot. For example, if our juniper was in a pot that is 3 inches deep, place a layer of soil in the tray that is 3 inches deep.

- Remove the tree from its original pot and sit it on TOP of the layer of wicking soil.

- Pour more wicking soil into the rescue tray so that the root mass is completely surrounded.

- Water the entire rescue tray thoroughly one time. Place the tray in bright shade.

- The next time you water, soak the rescue tray thoroughly with a systemic fungicide (see the June newsletter for suggested chemicals to use.)

- After applying fungicide, monitor the tree VERY closely. Water ONLY when the wicking soil is dry 1/2 inch down. When watering, try to put the water only on the wicking soil, and avoid watering the root ball.

The less water-retentive composition and larger particles helps excess water move away from the existing root mass, thus drying out root fungus. It also encourages new roots to grow in search of a source of water. A more open structure also increases the amount of air available for root metabolism.

Overpotting into wicking soil mix is a useful rescue tool to have in your kit, but it is not without risks. Certain bonsai enthusiasts even claim overpotting is overtly harmful. The following two articles provide a more in-depth discussion of the issues of overwatering and overpotting, I recommend you read them before you need them, and decide for yourself what to believe.

49.3.1 Another Treatment for Root Rot

This section was written by Michael Persiano and originally posted to rec.arts.bonsai on May 19, 1997.

If you suspect your bonsai has root rot, I recommend that you promptly remove it from the pot and examine the roots. Should you find rotten, soft mushy roots with black cores, execute the procedure for the treatment of root rot.

The procedure is straightforward.

- Remove the specimen from the pot.

- Cut away the rotten roots until white core is visible.

- Rinse away the soil and re-inspect for rotten roots which might have been concealed.

- Soak the specimen in a solution of Benomyl or Funginex for 5 minutes. This should be a full-strength solution based on the manufacturer’s instructions. A diluted mixture will not do the job.

- Scrub the pot and then repot the specimen using fresh, quick-draining soil. (The goal here is to provide the minimal amount of water required to sustain the life of the tree.) Be careful to work the soil into the root pad with a chopstick to insure optimal root-to-soil contact.

- Water the specimen into the soil with a solution of Superthrive. Water with Superthrive every time you water for the next 2-3 weeks. (Insert a chopstick into the soil and use it as a watering gauge. When the stick is on the dry side, water thoroughly)

- Place the repotted specimen in indirect light for a period of 2-3 weeks, and then gradually reintroduce the bonsai to direct light.

This method will not harm your bonsai: it will restore the specimen to its original state of health.

Important: in 7-10 days, submerge the potted specimen (to the level of the soil) in a bath of one of the above-mentioned fungicides for a few minutes to complete the fungicidal treatment.

49.4 Herbal Invasions

Sometimes when my pots get infested with star grass or other tough perennial weeds, I get an almost zen-like personal satisfaction from hand-pulling every tiny weed, but invariably some remaining root fragments re-sprout. If you are tired of losing this battle, or have weeds that would damage tree roots if pulled, there is a very potent alternative available: Roundup!

Many gardeners are nervous about using Roundup or other herbicides containing glyphosate. Used properly though, glyphosate is one of the safest pesticides on the market. It works by absorbing into green leaves and stems, then migrating to a plant’s roots and blocking an essential enzyme. Glyphosate cannot travel through bark or soil, and is degraded by soil bacteria into harmless metabolites. So if you have a tree that has a severe infestation of perennial weeds, try this technique rather than risking tree root damage.

- Purchase a small container of pre-mixed, ready to use Roundup or a generic equivalent. Make SURE the formulation contains glyphosate only.

- Pour about 1 tablespoon of the mix into a glass bowl.

- Soak a Q-tip in the glyphosate. Use it as a brush to paint the leaves of the star grass or other aggressive perennial weeds in your pots.

- Glyphosate requires 30 minutes or so to migrate into leaves, so if you accidentally get some of it on the leaves of the tree, pinch them off immediately.

- If you get glyphosate on the bark, do not be concerned. It does not move through woody surfaces.

- Wait at least 2 hours and preferably overnight before watering, so the glyphosate has time to migrate into the weeds.

That is all there is to it. For several days the weeds will look like nothing happened, but then suddenly they will turn limp and begin to yellow. Do not pull them out just yet, because some root tips are still alive. Wait until the weeds have gone completely brown, which may take 2 weeks. Then pull them with forceps.

1.  2.

2.

Image 1. English ivy 3-4 days after spraying with glyphosate. Image 2. The same patch after 2 weeks. Link to original image 1, by David Stephens, Bugwood.org.; Image 2, by David Stephens, Bugwood.org..

49.5 Mending Broken Branches

That sickening “snap” of a branch is the bane of all enthusiasts. A completely severed branch is not likely to survive, but if you work quickly, most partly broken branches can be mended. The key is to have the necessary materials on hand.

I have read several different methods, and each author recommends something slightly different. Some prefer raffia, others plastic grafting tape. Personally I have had good luck using regular floral tape. If you do not know what this is, it is the slightly sticky, slightly stretchy tape used to seal the ends of flowers for corsages. Floral tape is sufficiently tacky to hold in place yet comes off cleanly. It repels water and pathogens from the wound site, yet still allows air flow. Rolls comes in green and brown, but you may have to hunt around a bit for the brown. I prefer brown just because the break is less obvious as it heals, and I also can use it to make inconspicuous padding for guy wires.

To mend a break:

- Immediately bend the two halves of the branch back together so the broken ends fit together as closely as possible.

- Seal the break with 1 layer of overlapping wraps of brown floral tape. Start wrapping the tape about 1 inch beyond the break, and wrap back TOWARDS the trunk. Overlap the wraps about half the width of the tape.

- When you are done, feel the tape over the break point. If the tape alone is holding the branch together, there is no need to splint it.

- If the break feels like it wants to push open, place a straight 2 to 3-inch piece of heavy wire along the length of the branch, on the same side as the surviving hinge of wood and bark.

- First tape the end of the wire to the branch beyond the break. Then GENTLY push on the break to close the gap.

- Wrap tape around the other end of the wire (you may need help with this). The anchored wire splint should keep the break from opening back up again.

- Place the tree in a shady area to recover. Each time you water, mist the foliage on the end of the branch past the break. This will lessen the stress on the leaves and let them continue to produce nutrients to help in repairing the break.

- After a year, the spliced branch will have healed as much as it is going to. GENTLY remove the floral tape, and tap the branch to see if it has knitted together. If the branch still feels too flexible, consider filling the remaining gap with exterior wood glue or epoxy putty. If the foliage has died, the break never healed, and you can cut off the branch.

A partially broken green branch, about the diameter of a pencil. There is still intact cambium on the lower side. Part of the goal is to straighten that out so it can re-attach to the woody part of the branch. Original photo by Dan Johnson.

Straightening a green break. Do not try to force it too hard; you risk tearing the remaining cambium layer. Original photo by Dan Johnson.

Initial wrapping with floral tape. This layer is meant to keep the cambium from drying out while it grows back together Original photo by Dan Johnson.

Adding the wire splint. The wire splint is not essential if the branch is light and small, but it really is a good idea to use one anyway. I prefer wire, but others prefer to use wood dowels or flat craft sticks. Original photo by Dan Johnson.

A fully wrapped repair. The outer layer of tape can be looser because it is meant to hold the wire in place, not seal the break from water loss. Original photo by Dan Johnson.

A fully wrapped repair. The outer layer of tape can be looser because it is meant to hold the wire in place, not seal the break from water loss. Original photo by Dan Johnson.

If you do not have floral tape, use what is available to you. It is MUCH more important to close the break quickly than it is to use the “right” tape. Once I broke a branch on a semi-cascade bougainvillea that was living in my office over the winter. All my tools were at home, and all I could find was black duct tape. I folded a piece of tape on itself to make a non-sticky strip that I could wrap around the branch to hold it together. A second strip of tape around the wrapping held it in place. Despite using less than ideal materials, the branch survived and knitted back together.