Chapter 4 Getting Started

During bonsai demos I meet many people who are interested yet reluctant to try their hand. Over time these reasons have come up time and again.

- They tried it once but the tree died. Usually I find they tried to keep a juniper or other full-sun species indoors.

- There are too many rules.

- It requires expensive special tools.

- Bonsai requires special imported, expensive, hard to find trees.

- It takes too long.

- They can’t imagine how intermediate steps lead to the final end product.

- There is no “kit” or “plan” they can use to try it out.

If you are a new practitioner or just want to try out bonsai, here are some ways to demystify the process and lower your entry barrier.

4.1 Relax - It’s Supposed to Be Fun

We learn many creative activities like drawing or music through a process of “follow the rules and instructions first, then experiment later.” Bonsai does not fit that model. We work with live, unpredictable materials from the start. Even the most basic rules about branch placement may need to be ignored in order to create a visually pleasing tree that tells a story.

Traditional bonsai and penjing styling rules help us create the illusions of depth, size, and greater age, but I think they scare off many novices. Don’t get wrapped up in all of the rules and formality of bonsai. When you are starting out, focus on creating a tree that you like. If your tree is healthy and evokes a feeling or memory of nature for you, then it is a success.

4.2 Limit Your Initial Investment

Many practitioners use specialized tools because they make short work of tasks we do routinely, and last for decades. They are not essential though.

A set of bonsai tools, from left to right: leaf trimmer; rake with spatula; root hook; coir brush; concave cutter; knob cutter; wire cutter; shears (3 sizes). While these tools make many tasks easier, they are comparatively expensive. This basic set retails for $100-400, depending on the quality of the steel in the tools. Link to original image.

A set of bonsai tools, from left to right: leaf trimmer; rake with spatula; root hook; coir brush; concave cutter; knob cutter; wire cutter; shears (3 sizes). While these tools make many tasks easier, they are comparatively expensive. This basic set retails for $100-400, depending on the quality of the steel in the tools. Link to original image.

You can put together a serviceable tool kit using household items, or buy starter tools from the Dollar Store, Harbor Freight, or hardware store discount bins. With a bit of scrounging you can put together a full set of tools for less than $40. You can move up to dedicated tools after you get some experience and recycle your starter tools for other purposes.

Your basic toolset will have:

| Tool | Purpose or Function |

|---|---|

| Bypass pruner | Cutting branches; usually your most expensive item |

| Fine scissors | Clipping leaves, new shoots |

| Short, heavy scissors | Clipping soft green branches, small roots |

| Angled wire cutter | Cutting wire, pruning branch stubs close to trunk |

| Needle-nose pliers | Twisting wire, heavier grasping and pulling |

| Medium (8-10”) forceps | Pull wires through close spaces, reach into root ball or crown |

| 2-3 pencils or 12” dowels | Use a sharpened one to probe tight spaces; use unsharpened ones to probe pots, tuck soil between roots |

| Roll of duct or masking tape | Making pads for guy wires, making temporary barriers to hold soil |

| Small bottle of yellow carpenter’s glue | sealing wounds and pruning cuts |

| Kitchen or packaging twine | Tying down branches; cotton works best |

| Package of 12- or 14-gauge single-strand wire | Heavy wire to anchor trees in pots, bend large branches |

| Package of 16- or 18-gauge single-strand wire | Medium wire for shaping most branches. Either insulated or uninsulated works |

| Package of 22-gauge single-strand wire | Guy wires, fine branch wiring |

| Toothbrush or small plastic bristle brush | Scrubbing dirt from roots, branches, tools |

I listed three sizes of wire, but you can skip the heavy 12/14-gauge wire, and use two pieces of smaller diameter wire. Often you can scrounge sufficient copper or aluminum wire scraps from construction site trash or from electrical installations. Strip off the insulation or toss the wire in a bonfire to burn it off.

4.3 Use Whatever Tools You Have

1. Pruners

2. Fine scissors

3. Heavy scissors

4. Needle nose pliers

5. Lineman pliers

6. Angled wire cutters

7. Wooden chopsticks and an inexpensive fork

8. Screwdriver root hook

9. Forceps

10. Brass wire brush

11. Soft whisk broom

12. Solid wire

An inexpensive set of bonsai tools can be assembled from common household items that can be purchased at dollar stores, or found in discount bins in a hardware store. Other items can be recycled trash Small scissors help with leaf trimming, the heavy scissors, root and green shoot pruning. Needle nose pliers hold and bend fine wire, and help with making jin. Lineman pliers will help you cut and bend heavy wire, while angled wire cutters do double duty as concave pruners and help with removing wire from branches. Chopsticks are good for probing, while a $1 fork can be bent to form a rake. An inexpensive screwdriver can be bent into a serviceable root hook. Forceps are essential for reaching into tight spots. A brass wire brush and soft whisk broom remove dust and debris. Leftover wire (this is 2mm in dia.) often goes into the trash after electrical installations.

Link to original image 1; image 2; image 3; image 4; image 5; image 6; image 7; image 8; image 9; image 10; image 11; image 12.

4.4 Start With Inexpensive, More Forgiving Species

I combed through several references and put together a list of woody landscaping and houseplants that tolerate common beginner mistakes. Some species respond quickly and positively to pruning or wiring. Others are more forgiving of mistakes in wiring or pruning or lapses in care. All can be repurposed if the beginner decides bonsai is not for them.

I left out some species that are recommended by others, but that I think are poor choices for beginners here in NC. For example, I did not include barberry and pyracantha because they are extremely brittle, the thorns are hard to work around, and both are prone to root rot.

I also left out dwarf junipers (Juniperus procumbens ‘Nana’). I know they have fans, but I found them more frustrating than enjoyable when I was first starting; they kept dying. They do well in pots in cooler climates, but here they seem more disease- and mite-prone. They do not tolerate being over- or under-watered, andy do not tolerate over-pruning errors well.

These are the species that I would pick for teaching first-timers, and why I like them.

Shore juniper (Juniperus conferta ‘Blue Pacific’). Some experts consider this a cultivar of J. rigida (temple juniper). It has a low spreading shape like J. procumbens ‘Nana’ but is more heat tolerant. For me it seems a BIT less fussy about living in pots, though it definitely needs well-drained soil.

13.

14.

Shore juniper. 13. A yellow cultivar. 14. A mat of recumbent foliage. Link to original images: image 13; image 14.

I think this is the best choice for a conifer because they are cheap and readily available. The needles are softer so the foliage is easier to handle, and they have long sinuous branches that can be wired easily to create dramatic shapes. Most landscape stock has one longer branch than can be wired upright into a leader with the rest of the soft branches drooping to the ground like a hemlock. One downside is that this species resents being pruned, so cuts should be made infrequently. Tips are best groomed by pinch-pruning rather than cutting.

Boxwood (Buxus sempervirens). Common boxwoods are evergreen but are not in the conifer group. They are available nearly everywhere. The big challenge is finding a starter tree that has one larger trunk with some surface roots rather than multiple small shoots. Beyond that, boxwoods tolerate root and branch pruning extremely well, have a naturally fibrous root system, back-bud nicely, and are not fussy about conditions. Branches are brittle after the green stems become woody, but they still can be wired with care.

Chinese elm (Ulmus parvifolia). Bonsai enthusiasts love the tiny leaves of super-dwarf cultivars like ‘Nire-keyaki’ and ‘Yatsubusa.’ These dwarf cultivars are fussy about growing conditions so are not appropriate for novices, but non-dwarf elms are great choices. They still have small leaves, grow quickly, and are widely available. Many nurseries and home centers carry landscaping sized trees that can be cut back and rebuilt in 1-2 years. They grow readily from seed; I have grown saplings 6 feet high and 1/2 inch or more in diameter from freshly collected seed in just 4 years. On at least three occasions I have found mature trees with dozens of transplantable seedlings beneath them. Chinese elms adapt to a variety of soil mixes, they tolerate radical pruning very well, and they will thrive even when their roots are crowded in the pot or ground.

15.

16.

Boxwood (15) and Chinese elm (16). Link to original images: image 15; image 16.

4.4.1 Other Options For Novices

These are in alphabetical order by scientific name, not by any preference.

Red maple (Acer rubrum). An eastern North American native. Red maple behaves much like trident maple in cultivation. Its three-pronged leaves even look a bit like trident maples. They tolerate conditions ranging from swamp uplands to dry poor soils. Red maple adapts to pots well and is very forgiving of lapses in watering. Trees can be purchased at any nursery, or dug from wild stands in late winter. The main drawback is they tend to have long branch internodes. Still, they are a forgiving trees for learning.

Hedge bamboo (Bambusa multiplex). Unlike invasive bamboos, hedge bamboos form clumps that will not spread quickly. This subtropical species is more cold-tolerant than most bamboos, so can be left out later to kill overwintering insect pests. However, hedge bamboos also are well adapted to life in pots, and also can live indoors for part of the year. Hedge bamboo is not well suited to single trunks, but forms nice grove plantings quickly. There are dwarf forms that top out at 3 feet high (B.m. ‘Tiny Fern’) and large forms (B.m. ‘Alphonse,’ ‘Golden Goddess’) that reach 20 feet. Most cultivars respond to small containers by reducing the height and diameter of the culms, as well as reducing leaf size. Hedge bamboo does not like wet feet, but it forgives underwatering well. When planting a grove from a potted plant, divide clumps into groups of 3-5 culms (main trunks) each.

17.

18.

Red maple (17) and hedge bamboo (18). Link to original images: image 17; image 18.

Butterfly bush (Buddleia sp.) The one challenge of butterfly bush is that it does not like small containers. When overpotted thought a butterfly bush will put on several flushes of growth that provide regular opportunities to practice pruning. Many colors are available. Novices can buy 5-10 attractive small bushes for the price of a single (often poorly) grafted Japanese maple.

Burning bush (Euonymus atropurpureus). They are widely used landscaping shrubs that require minimal care. Many people do not realize these are native to Midwest North America, from Ontario to Texas. They are slower growing than some of my other recommendations, but provide year-round interest with flowers, fruit, and brilliant fall color.

19.

20.

Butterfly bush (1) and Euonymus (2). Link to original images: image 19; image 20.

Banyan fig (Ficus microcarpa). I did not choose weeping fig (F. benjamina) because it has a habit of dropping leaves and undergoing twig die-back. Banyan figs are harder to find initially, but they grow in height and girth more quickly. These MUST come indoors once night-time temperatures fall below 50o F.

English ivy (Hedera helix). Older ivy vines with thick woody bases often can be dug up for free. Breaking off feeder roots during transplantation is not a concern, since they will quickly regrow. Ivy tolerates extremely hard pruning, and back-buds readily.

21.

22.

Banyan fig (21) and English ivy (22). Link to original images: image 21; image 22.

Japanese holly (Ilex crenata). Not an especially attractive shrub and a bit brittle but it tolerates pruning very well. Shrubs with large bases are reasonably inexpensive. In my experience potted specimens prefer semi-shade here in NC to keep the roots cool.

Nandina (Nandina domestica). This shrub is in the barberry family. Many people dislike nandina because it is invasive, but that means there are a LOT of shrubs available to dig out for free. In pots, it develops airy foliage pads like sparse Japanese maples or bamboos. Nandina is nearly indestructible; cut it to the ground, and the stump will resprout quickly, so any pruning and styling mistakes can be cut out completely.

23.

24.

Japanese holly (23) and nandina (24). Link to original images: image 23; image 24.

Confederate jasmine (Trachelospermum jasminoides). A fast-growing vine that can reach 25 feet and bears sweet-smelling white flowers all summer. It adapts well to life in a pot, but needs good loam soil, partial shade, and consistent moisture. A strong woody base forms in just one year, and regular side shoots provide plenty of material for pruning and shaping practice. This species has no problem being cut back regularly, so is good for learning how to build trunk and branch taper.

25.

26.

25. Confederate jasmine growing on a wall. 26. a cascade bonsai made from the Asian jasmine, a related species. Link to original images: image 25; image 26.

4.4.2 Woody Herbs Are Another Option

Richard W. Bender published an unusual book entitled “Herbal Bonsai” (ISBN 0-8117-2788-2). He describes how woody perennial herbs and sub-shrubs can be made into interesting bonsai in one growing season. Unlike traditional bonsai, the goal of herbal bonsai is not to increase trunk size over several years. The plant is trimmed to a basic skeleton and planted out in late spring. It is allowed to grow on until mid-September to increase branching and foliage density, then is lifted and potted up. Final shaping takes place in autumn.

Herbal bonsai provide a rewarding specimen for a small investment of time and money. Herbal bonsai also builds confidence and provides frequent opportunities to practice pruning and shaping. The trunk size is largely pre-determined by the size of the starting stock plant. So it is a good idea to buy an herb plant that is fairly large if possible.

Herb species that can be used include:

- Southernwood (Artemisia abrotanum)

- Wormwood (Artemisia absinthum)

- Bay laurel (Laurus nobilis)

- Common myrtle (Myrtus communis)

- Marjoram (Origanum majorana)

- Scented geranium (Pelargonium sp.)

- Lavender cotton (Santolina chamaecyparissus, S. virens)

- Germander (Teucrium sp.)

Mr. Bender recommends rosemary too, but I do not. Rosemary is very fussy about soil, and here in the Piedmont it is prone to both mold and die-back. This is not going to inspire confidence, which is why I would choose something else.

4.5 Use Shortcuts That Make Styling Easier

These are some ways to modify standard styling practices so they are less intimidating for novices.

- Over-pot trees. Small pots restrict growth and dry out quickly. When a small tree is overpotted in an attractive container it is less likely to dry out, and will recover more quickly from pruning and watering mistakes.

- Use cotton twine to pull down branches instead of wire. Twine is soft enough to form its own pad around limbs. An open loop tied around a branch is unlikely to girdle a branch before it rots through.

- Bend large branches using template wires rather than spiral wiring.

- Cut a single piece of wire twice the length and 1/4 the diameter of a branch to be bent, then fold the wire in half.

- Lay the doubled wire beneath the branch so the two halves straddles the branch, then tie it in place with wide rubber bands.

- When the branch is bent, the wire will slide but should still hold the branch in place. The rubber bands will stretch as the branch diameter increases, and they will break down in the sunlight before creating a scar.

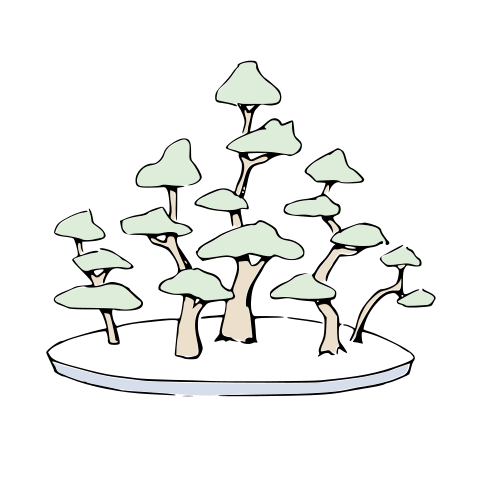

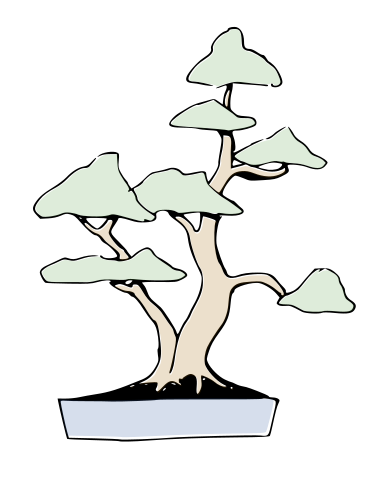

- Use less traditional styles that achieve a dramatic look quickly. Raft styles are very easy to create (especially in deeper containers), as are clump, multi-trunk and forest styles.

Styles that are easier to develop more quickly. 27, 28: raft style. 29, 30: forest style. 31, 32: multi-trunk style. Links to original images: 27; 28; 29; 30; 31; 32.

4.6 Shorten Your Time to a Final Product

Long-term practitioners see our trees as ever-changing puzzles to be solved. Slowly, patiently building new branches and foliage pads is part of the fun. When first starting, waiting even a month is hard, let alone a year. Don’t use clip-and-grow techniques. Build your tree out of the currently existing branches and foliage.

4.7 Pay Attention to Aftercare

Make sure you know how to care for the finished tree. Write out a “care card” for each tree you create. Include:

- How to gauge when soil is too dry, too wet, or just right.

- How much light the particular species likes.

- When and how much fertilizer to give the tree.

- Signs that it is time to repot the tree, and when to do it.

- Early warning signs of problems:

- Discolored foliage

- Wilted leaves even after watering

- Early leaf drop (deciduous trees) and browning needles (conifers)

- Where, how to protect the tree during cold weather.

Remember, nearly all bonsai belong outside. Even tropicals prefer being outdoors for our hot, humid summers.